The most accurate way to think of the Chartreux is as ‘native French blue cats’. The late Jean Simonnet tried to find out the origin of these cats by studying various old documents, documents that he later published in his book ‘Le Chat des Chartreux’ and in which he writes:

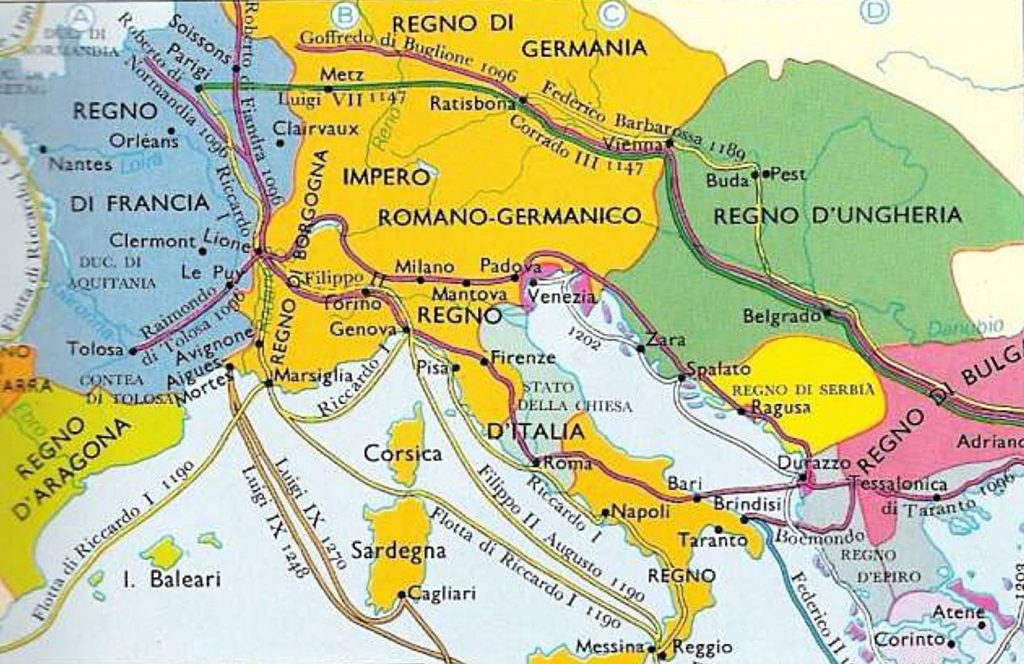

I am inclined to think that these blue cats originated in the rugged, mountainous regions of Turkey and Iran, from where they were probably brought into the neighbouring territories of Syria. Their unique coat indicates that they lived in damp areas with cold nights and harsh winters.

If that assumption was correct, they were probably brought to France by returning Crusaders or merchants along the ‘Silk Road’ in the 13th century.

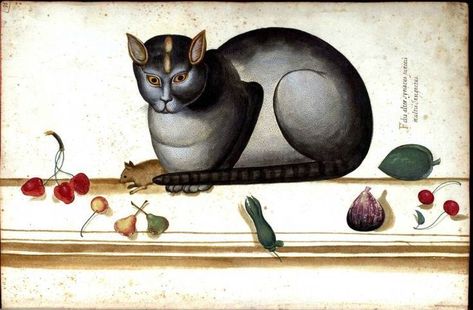

Stories of these blue cats began to emerge during the 16th century. Ulisse Aldrovandi described the ‘Cat of Syria’ with a blue coat, stocky body, developed jowls, two eyes of astonishing colour and slightly almond-shaped. The mouse at its side marked its rodent-hunting characteristics.

Legend links these blue cats to the Carthusian monks who lived in the Chartreuse Mountains north of Grenoble. But, in 1972, the Prior of the Grande Chartreuse stated that their archives did not show that they had kept cats. However, it is very possible that some cats found their way to the monastery, where there must have been lots of rats and mice.

The first written document mentioning these blue cats was a poem written by Joachim du Bellay in 1558 entitled ‘Vers Français sur la mort d’un petit chat’.

First of all, then, let me say,

Belaud was not wholly grey

As cats which in France are born,

But like those which Rome adorn.

Belaud was not one of the French cats that he refers to in this verse of the poem, but came from Italy and looked quite different, which he describes in other verses.

The name Chartreux was first mentioned in the ‘Dictionnaire Universel de Commerce’ by Jacques Savary des Brûlons, published in 1723, in which it was defined as:

the common name of a type of cat which has a blue coat. Furriers do business with their pelts.

The exact origin of the name remains unclear. But, because of the soft and woolly character of the coat, it is quite possible that these cats were named after the luxurious Spanish wool ‘la pile des Chartreux’.

Although known as ‘the cat of France’, they were also referred to as ‘the cat of the common people’. It is quite possible that, in addition to natural colonies in the 18th and 19th centuries, people raised them for their pelt and meat and as ratters, so they did not lead easy lives.

As Jean Simonnet noted in his book, whilst Persian cats were celebrated by poets, treated like princes and were companions of royalty, the Chartreux wandered the streets of Paris fending for themselves and always in danger of losing their lives for their pelt.

But some Chartreux were more fortunate. Jean-Baptiste Perronneau’s painting ‘Magdaleine Pinceloup de la Grange’ from 1747 clearly shows a blue cat as a pampered pet.

This is what the J. Paul Getty Museum says about this painting:

With both hands, Magdaleine grasps a large blue cat that bemusedly engages the viewer. Because of its large size and distinctive colouration, the cat can be identified as a Chartreux, one of the oldest and most cherished French breeds.

Jean-Baptiste Perronneau included feline companions in several of his portraits of female subjects, reinforcing the elegance and sophistication of his sitters. Here, the bells on the Chartreux’s collar echo the pearls around Magdaleine’s neck, suggesting that cat and sitter alike are refined objects for visual delectation.

The 18th-century naturalist Linnaeus described the Chartreux in great detail and gave it the Latin name Felis Catus Coeruleus, blue cat, differentiating it from the common Felis Catus Domesticus, the domestic cat.

Although there was not a large population, natural colonies of these cats were living in Paris and in some isolated regions of France until the early 20th century. However, the first and second world wars were to decimate the breed. After WWI, no major breeding colonies of Chartreux were known to exist, so some French breeders became interested in preserving this ancient breed for posterity.

One colony was found living on the island of Belle-Île-en-Mer off the coast of Brittany. They were known locally as the ‘hospital cats’ as they lived in the grounds of the local hospital. The Léger family moved to Belle-Île in about 1925. Their daughters Christine and Suzanne had studied at the School of Horticulture in Versailles and were very interested in breeding animals. On the island, they came across many beautiful blue cats, and if the name ‘Chartreux’ in the 18th century meant ‘native French cats with a blue woolly coat’, then these cats matched that description. They began monitoring the cats, helped to care for them, and eventually began selective breeding under the cattery name ‘de Guerveur’. The results were excellent in all cases, but the colour of the coat and the eyes varied, which is common in pure selective breeding. The temperament of these cats was one of remarkable mildness.

In 1931 ’Mignonne de Guerveur’ was judged to be the most beautiful cat in the Paris show, and in 1933 she became International Champion and Best Cat in a show organized by Cat Club de Paris.

After the Léger sisters had started the breeding, Cat Club de Paris began breeding with blue cats from a colony in the Massif Central, a highland region in the middle of Southern France. But in 1936, they acquired a male Blue Persian, Japouk du Fouillox, to improve the eye colour and mated him with Titote, a feral cat. WWII severely curtailed their efforts, but one of their sons, Keekey de Champol, survived the war and was mated with Trisette, a feral cat, and became father to a boy in 1948 named Weekey de Trevise. He was to play an important role in the Cat Club’s breeding programme. In 1950, Dim and Zolouska, both feral cats, had a son, Vasska, who resembled the cats of Belle-Île, and he was mated with Grichette de Sytka. In 1960, he became father to Jimmbo, a remarkable cat who is in the pedigrees of most modern Chartreux. Weekey de Trevise and Jimmbo are also in some de Guerveur bloodlines.

By the mid-1960s, the Cat Club’s stock was very inbred. The breeders at that time lacked knowledge of the history of the Chartreux, and they did not know that their predecessors had selectively bred and improved the cats in their breeding programme. Instead, they started to cross-breed them with the British Blue Shorthair. Despite that, the Léger sisters obtained another male from the Cat Club in 1970, and they had excellent results when mating him with their females. The characteristics were maintained, and the eye colour improved.

At the same time, Mr Simonnet acquired two females from Belle-Île and started breeding under the name ‘Chatterie du Vaumichon’ using males from the Cat Club. Many Chartreux breeders consider Mr Simonnet to be the one who saved the breed.

In 1970, Fédération Internationale Féline, FIFe, made the unfortunate decision to assimilate the Chartreux with the British Blue and adopted the British Blue standard for both breeds. If this had continued, the Chartreux breed would have died out. This led to strong protests from the few remaining breeders of the Chartreux, and after a lengthy battle, in 1977, FIFe decided to separate the British Blue and the Chartreux and to introduce a breed standard for each breed. Cross-breeding is now not allowed by LOOF, CFA and TICA and FIFe state:

A clear distinction should be drawn between the Chartreux, the Russian Blue and the British Blue. Crossing the Chartreux with these two breeds is undesirable.

DNA tests on modern Chartreux have shown that, despite having some ancestry in common with the British Blue and the Persian, as do other breeds with origins in Europe, the Chartreux is clearly a separate breed with its own distinctive DNA signature.